Happy MAG-nificent Monday!

3-Macro: 3 stories impacting the competitive environment in which we operate

Hike shuts down after India RMG ban

Why GenAI is failing

Amazon and Netflix announce Gaming+Streaming bundle

2-Alpha: 2 potential sources of Finding Alpha

Clash Royale hits 3 year all-time highs… how?

The Illegible Margin (by Taylor Pearson)

1-Game Dev: 1 lesson learned from getting my ass kicked in game dev

The Problem with Product Validation

This week one other slight tweak. Instead of doing text summaries of the Alpha and Game Dev podcast content, I just transcribed the text below. Which do you prefer?

Check it out! 👇👇👇

Brought to you by:

Stash: The only full-suite D2C platform built for game studios ready to win. Stash goes beyond payments with loyalty, incentives, and conversion tools that turn transactions into growth. With Stash, you don’t just go D2C—you grow D2C.

3. Macro

Top 3 Most Significant Gaming News From Last Week:

Hike Shuts Down After India Bans Real-Money Gaming (TechCrunch): Former unicorn startup Hike is shutting down completely after a new Indian law banned all real-money online games. The regulation fatally undermined the business model for its gaming platform, Rush, making its primary market unviable and prompting the 13-year-old company's founder to cease all operations.

Naavik: India’s Post-RMG Era

Why Generative AI Projects Fail (Computerworld): Generative AI projects often fail not because of technological limitations, but due to fundamental issues with strategy and implementation. Key reasons include a failure to identify a clear business problem, leading to solutions without real-world value. Many projects also falter by starting with the technology itself rather than the user's needs, resulting in a poor user experience

Marcus on AI: Generative AI’s crippling and widespread failure to induce robust models of the world

Unity Podcast: Confessions of an AI Maximalist with Joe Kim

JK’s First Post on AIxGaming in 2022: Mr. Beast, Tesla AI Day, and the Future of Game Development: Small Vector Creation is Coming!

Amazon and Netflix Strike Major Ad Platform Partnership (The Hollywood Reporter): Amazon and Netflix have partnered to bring Netflix's ad-supported tier inventory to Amazon's DSP (demand side platform), starting Q4 2025 across 11 countries. Amazon now can programmatically buy advertising across all major U.S. streaming services through its DSP, despite owning the competing Prime Video platform.

2. Finding Alpha

Alpha Insight #1: How Did Clash Royale 5X Revenue?

For our first Alpha insight, we are looking at the recent revenue explosion from Clash Royale last month. You might think it's an old, declining game from March 2016, but Supercell has done it again. Just like Brawl Stars last year, Clash Royale is now having its moment.

Let's start with the headline number because it's a banger. According to AppMagic data, Clash Royale pulled in over $68.1 million in revenue in August. This is the kind of revenue the game hasn't seen since the summer of 2017. We're talking about a nine-year-old game hitting numbers from its peak glory days. For example, back in December 2017, they made a little over $80 million. For more recent context, Clash Royale was making just $12 to $15 million per month throughout late 2024 and early 2025. We're looking at a 4-5x increase since the beginning of this year. These aren't just small improvements; this is a complete renaissance.

In fact, Clash Royale out-earned both Brawl Stars and Clash of Clans combined in August. I also want to point out some additional data points I found from SQURS.com.

In terms of new accounts per year, Clash Royale was on a steep decline from 33 million in 2021 to 16 million in 2023 and just under 13 million in 2024. But now, in 2025, the turnaround is fully underway. SQURS is showing roughly 12.6 million new accounts so far, which is about the same as all of 2024, with three and a half months left to go, including Christmas. So 2025 will dramatically outperform 2024.

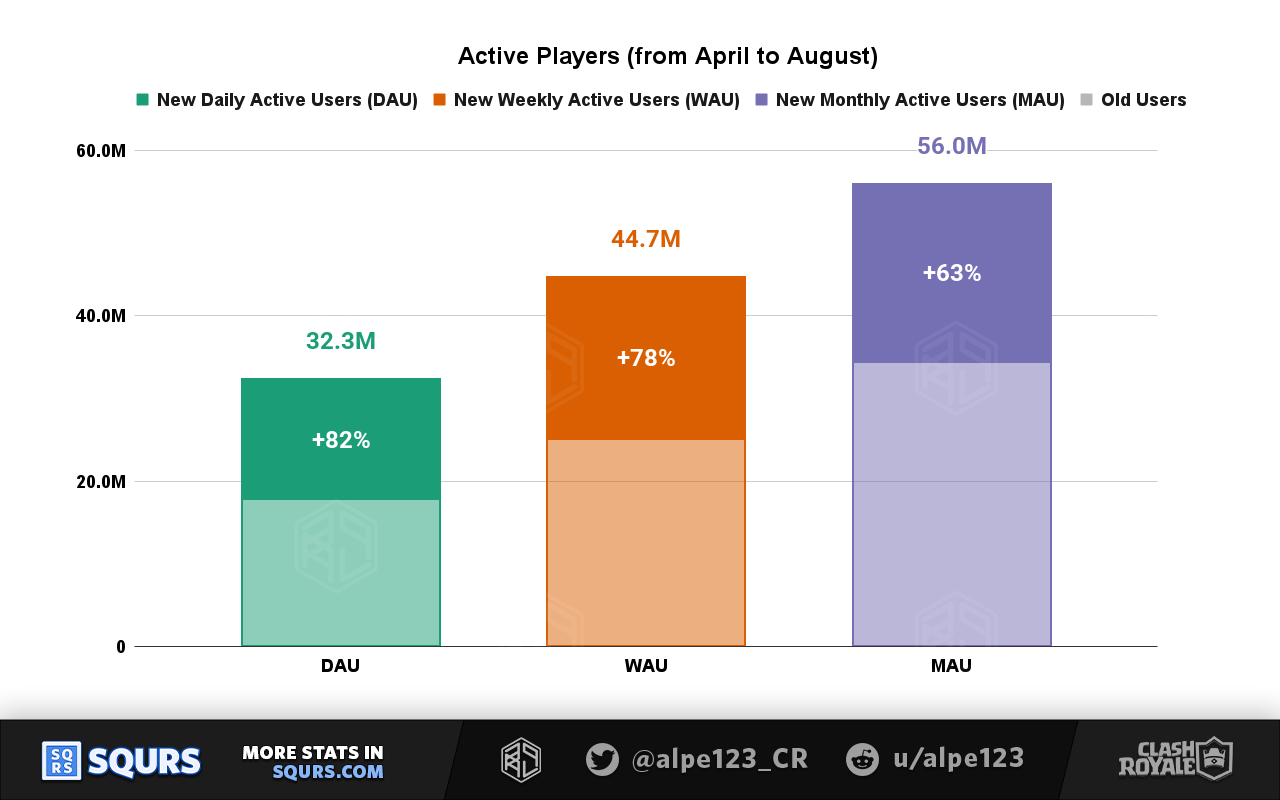

SQURS is also showing 56 million MAU in August, up 63% since April. Total accounts have increased by 4 to 10 million, but active users have increased by 30 million, which means significant reactivation.

So, what happened? What did they do? Oddly enough, the primary changes seem to be along the lines of product, live ops, and growth. Let's look at each of these areas.

Starting with product, they made a number of changes beginning in April, including the elimination of chest timers. They removed chest keys, killed banner tokens, simplified the season shop, expanded the battle pass from 60 to 90 tiers, and merged daily rewards with battle rewards, shifting to instant gratification. The June 2025 update overhauled progression: Trophy Road stretched to 10,000 trophies, ranked mode got seasonal resets, Masteries got nerfed, and resource tweaks were introduced to help casual players.

Then, in July, they introduced what I think may be one of the biggest factors: a new major mode called Merge Tactics. As you can guess, it's a four-player, turn-based auto-battler mode. Just like Riot added Teamfight Tactics to League, Supercell added Merge Tactics to Clash Royale.

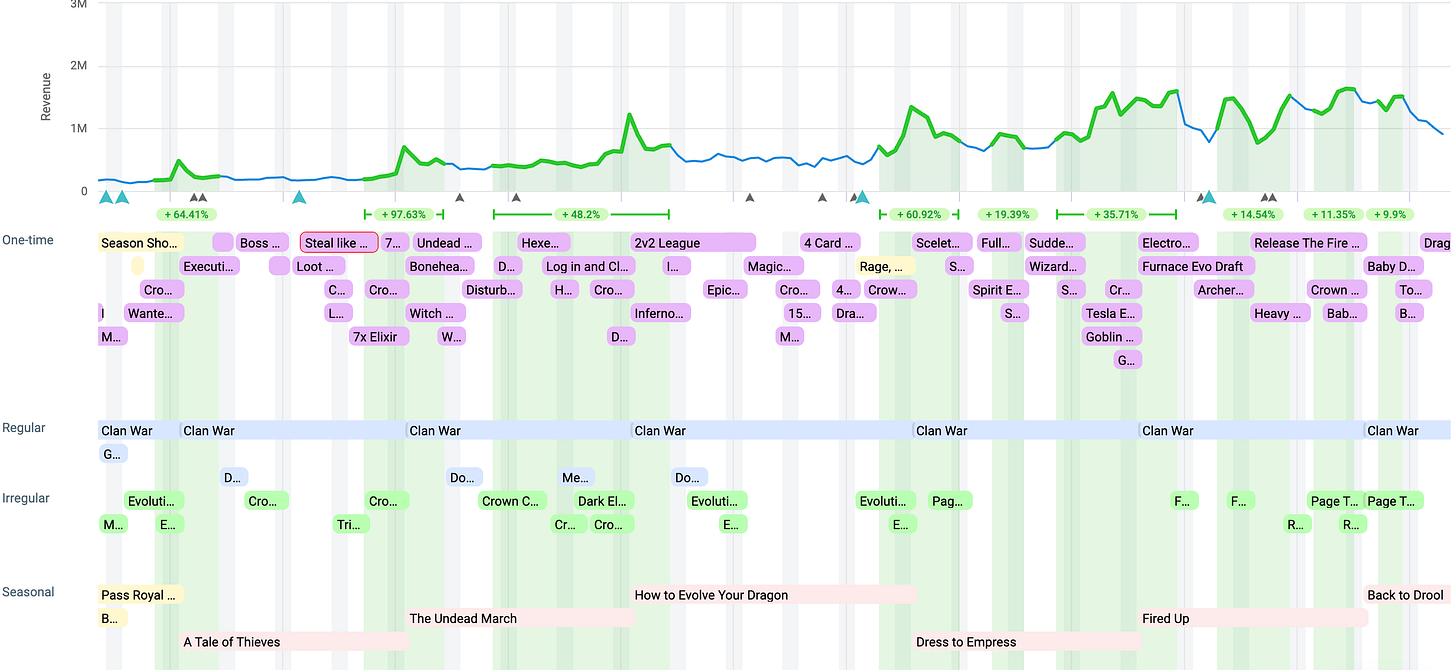

On the LiveOps side, they've gone berserk. The Clash Royale LiveOps calendar is jam-packed. They're rotating everything, bringing back old favorites like 2v2 mode, reskinning old formats, and just throwing a constant stream of one-time events at players. It's hard to get bored. On top of that, they expanded the meta with Card Evolutions. This seems to be a major driver on the LiveOps side. It's a new, deep progression system that creates a whole new power chase for veteran players. This feature forces everyone, even maxed-out whales, back on the progression treadmill.

In the final area, growth, this is a big one. I was speaking to a UA expert at a game dev lunch I hosted, and he confirmed that the word on the street is that Supercell has changed its stance on performance marketing. The theory is that they are now way more aggressive with UA than they historically have been. For a decade, the narrative around Supercell marketing was rumored to be just making a great game and running brand campaigns. What I'm now hearing is that they are pumping a ton of cash into targeted campaigns, especially after the June update, with downloads jumping 20-30% month-over-month in key markets. There are rumors about heavy ad spends on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube.

On top of all that, they got a lot of free promotion from creators. Influencers like Jynxi and Ken had streams and meme edits that went viral, and even Mr. Beast jumped on at one point. All these changes in product, live ops, and growth are leading to a virtuous cycle of increased engagement, ARPU, and spend on growth, which leads to more attention and viral promotion from influencers.

There you have it. Supercell does it again, this time with a full slate of initiatives that kicked some ass. Take notes, everyone. Supercell, with Brawl Stars last year and Clash Royale this year, is teaching a masterclass on reviving legacy franchise games.

^^ Free for a limited time

Alpha Insight #2: Understanding the Illegible Margin

Alpha Insight number two is about the concept of the "illegible margin," which was first documented in a book called Seeing Like a State by James C. Scott.

I became aware of it a few years ago when someone sent me an essay by Taylor Pearson summarizing the book. Last Friday, I was talking to my buddy Corey Klein from Fateless Games and getting feedback on a new product validation framework I had designed when he suggested I read that same essay. The first time, I think I just skimmed it, but this time I took the time to read through it, and now I get the point.

Let me start by reading the first few sentences from that Taylor Pearson essay:

Margin, in a strict business sense, is the difference between how much you can sell a product for and how much it costs to produce.

In a more general interpretation, margin refers to the edge of something, the amount which something falls short of or surpasses another item.

You can build margin into your day by leaving a gap between your scheduled meetings and tasks so that you have room to be flexible. You can have margin between how much money you earn and how much money you spend, so that if something unexpected comes up, you can afford it.

But not all margin is easy to see, and finding previously unseen margin is incredibly valuable.

The huge growth in mobile usage over the past decade has shown that those little pockets of margin—between meetings or commuting during the day—add up to a lot. Smartphones, less than a decade old, are surpassing PCs on their way to 5 billion users.

There are a few nuanced interpretations of this concept, but let's start with the basic idea. The book Seeing Like a State is all about how governments and big systems try to make the world legible for control and measurement. But what they end up doing is screwing over the messy, valuable, complex stuff that's hard to measure. The book suggests that states try to simplify everything into grids and metrics to see it better and control it. It's like the Peter Drucker saying, "You can't manage what you can't measure."

The specific example given is 18th-century German foresters who turned wild forests into uniformly designed and planted pine farms, structured in a highly organized way so it was easier to do timber counts. The short-term win was that more logs were sold, and it was easy to calculate the number of trees. The first-order effects were achieved, and it was easier to measure. But then came unintended second- and third-order effects: the forests started dying from pests and soil rot because the state ignored the illegible part of the forest—things like biodiversity, underbrush for animals, or mixed trees for natural balance. A bunch of complicated factors associated with the natural way forests grow didn't happen in these highly structured forests. While they made measurement easier and more predictable, they effectively killed the forests.

A second lesson from the book is about what Scott calls "high modernists"—people highly focused on top-down, authoritarian rule with a blind faith in structured, measured planning. As an example, the book mentions building Brasília in the 1950s as a perfect grid city to modernize Brazil. The end result was a sterile ghost town where nobody wanted to live. Compare that to more organic cities like Brooklyn that evolved in a bottom-up, messy way, with shops under apartments, mixing life with business. That was much more successful.

One last lesson from the book is the concept of value found in the illegible margin. Taylor Pearson talks about the little pockets of margin that mobile phone users have, as I read earlier—small bits of time between meetings or commuting. This all adds up. He suggests it was difficult to see the massive growth in mobile usage because these small bits of time are difficult to measure. They are, in effect, illegible. But it's here, in these illegible margins, where the real value hides.

Let's recap the lessons. First, we should be careful about too much top-down, authoritarian planning. Some processes can have detrimental second- and third-order effects by pushing a specific KPI too much. We may achieve a North Star metric and win a battle but ultimately lose the war. To mitigate this, the Microsoft Outlook team for mobile is famous for trying to achieve specific KPI targets but then ensuring they also compare any big feature change against key health indicators like engagement to ensure there weren't any negative impacts they couldn't account for ahead of time.

The second lesson is about the dynamic between top-down, pre-planned structures and organic iteration. This is a common duality that parallels others, like the two archetypes of creating art: conceptual innovators versus experimental innovators, as described in the book Old Masters and Young Geniuses. I depart a bit from the book in that I would not suggest everything needs to be bottom-up and organic; you should understand the duality on both sides and draw from both.

The final lesson goes back to finding alpha. Where do we get our competitive advantage? According to Seeing Like a State, you should explore the illegible margins and find the great value hidden underneath the surface, hidden by things that aren't necessarily measured. I'll come back to this concept in the future, but for now, I highly recommend you at least read the essay. Think about this concept more deeply. It's a very cool concept with great lessons to learn if you want to be successful and find that alpha in your game development studio.

1. Game Dev: The Problem with Product Validation

Last section, Game Development. For some reason, I'm always running out of time here. I have a hell of a lot of work, and I'm not sleeping much, but I'm doing this for you. Well, it's also good for me to spend time reflecting on macro, competitive advantage, and game development. If you appreciate the content, please give a like, share, or comment because it really helps.

For today's game development lesson, I wanted to talk about an issue we have been struggling with at our studio, one I've been thinking about a lot: product validation. Let me start with what I believe to be a typical philosophy by many game studios, executives, and investors when it comes to product validation—some call it player validation or market validation. What I'm talking about is trying to determine whether the game you are working on will be successful. This generally involves either qualitative or quantitative data analysis to give you an indication of whether your game design, if properly executed, can lead to success.

I actually believe most people are not making good use of their time or resources in product validation. From my own experience, I have seen a number of very time-consuming, expensive product validation initiatives that were highly intellectual but, in my opinion, just yielded fancy numbers, a fancy-looking report, and a lot of theory that didn't impact the product at all. In the worst cases, fancy product validation consulting firms have executed costly projects that actually hurt the product.

In my career, having worked studio-side and led a number one top-grossing game with zero product market research, and having been involved in dozens of market validation studies, I have to say there is value to concept testing. But a lot of the initiatives I've seen around feature validation, personas, or player motivations—at least the personas that were not data-driven—had extremely limited to no value. In fact, speaking to a few extremely smart and experienced game development leaders in the past few weeks, one who is the head of R&D at a famous studio told me something similar. With respect to player motivation analysis, he also has not really seen anything demonstrably valuable over his career. Another famous gaming leader who created one of the biggest games in the world mentioned something that stuck with me: does talking to and getting data back from a bunch of random people actually give you more signal, or does it just give you noise?

With that context, let me tie this back to what we discussed in Alpha, from the book Seeing Like a State. Do you see the connection? Executives, investors, product managers, and studio leads all want certainty. They want an answer to whether a game will be successful as early as possible. In short, they want to measure success. The fundamental question they are trying to answer is, "Will this game be successful?" But if we think about the illegible margin, another question we should ask is, "Is this question even measurable, or are we yet again trying to measure the illegible?"

It's a real concern because the other issue with product validation is that it is extremely complicated. That head of R&D I spoke to did suggest it can be valuable, but it is extremely complex to execute. Yet, when I speak to so many gaming executives or investors, I hear time and time again, "Did you do the product/market/player validation?" The problem is that they see this as a binary checklist item. "Oh, you did it? Great." or "Oh no, you need to do it." But it's not binary. It's not about whether you did it; the bigger question is how you did it.

The prevailing narrative is, "You have to do the player validation as quickly as possible. Just do it." "Okay, we did it. Check." "Great, they did the player validation. They're fine." But the vast majority of these people just don't have a clue what they are talking about. They have a high-level conceptual idea, but the fact is, there are a million ways of doing this, and probably 999,999 bad ways. Honestly, I'm not sure if I've ever done it in a good way or even seen it done well, and I've been in this industry for a long time. I will caveat that with concept testing; there's a lot of good stuff there. And building personas out of data through clustering can be useful. But during the game development phase, a lot of validation is just extremely difficult to do.

To make this more real, let me describe a scenario where this kind of player validation could go wrong. Imagine you're working on a big-budget game with a lot of risk. Executives are worried about the gameplay, so you hire a consultant to do player validation. You want to take the game in a MOBA direction, or maybe an RTS direction. This consulting firm, some of whom have never made a game, will then do a broad-based survey with a lot of players. They'll ask questions about concept art and gameplay models like a MOBA, an RTS, and city building. They ask players what they want.

The thing is, many players, unlike experienced game designers, can't conceptualize high-concept things. So they might just say, "We love MOBAs, we love RTS, we love city building. You should just put it all together!" This actually happened. And it was a wrong approach. Players are not game designers. Depending on how you frame the question and execute these surveys, you can get all manner of feedback. The execution counts. In this particular case, they launched a Frankenstein game that made no sense because "the players said they wanted a MOBA and an RTS and city building." It was a disaster.

The point I'm trying to make is that this is not an exceptional case. I have seen so many bad validation studies. There is so much nuance and complexity that you can easily go wrong. It can lead you to a point where you're not just wasting time but actually getting more noise than signal and going in the wrong direction.

So what do you do? I'm not saying all validation is bad. There are likely good ways of doing it, but it's very difficult to execute properly. Let's characterize the kinds of validation possible by stage. Since I'm mobile-centric, I'll talk in that context: pre-production, production, soft launch, and hard launch.

During the pre-production phase, I have seen some types of validation that are useful, which is concept testing—testing a high-level game idea. For example, testing a game concept where you combine an IP with a new genre. While there are bad ways of doing this, there's some maturity here, and it can give you good signal. The hyper-casual guys are masters of this. They test video creatives of a game they haven't made yet, use a fake app store, and look for high IPM (impressions per mille) and CVR (conversion rate). This can give you a rough idea of whether players would react positively and can lead to good estimates for CPI. It can also be done for relative testing, like comparing a World of Warcraft 4X, a Pokémon 4X, or a Naruto 4X. You create the creatives and test them. This kind of high-level concept testing can work.

Then in production—ideally, in pre-production, you'd also have a sense of the features. This is where we get into trickier territory when we try to use validation to drive feature design. This can take the form of frameworks around player motivation and personas, hypothesizing the kinds of players who would want your game and prioritizing features for them. To be fair, there are likely folks who have done this well. I know Riot has thought about this a lot. But I don't think the majority of the industry has this figured out, and I include myself in the clueless majority. So I am not in that successful minority, if there is one. Sometimes I think this question might be part of that illegible margin.

Another way this is done is through things like customer satisfaction surveys, where you ask players what they think about certain features and score them. But again, this comes down to execution. I have done concept tests where putting a gradient on one character versus another makes a difference. The quality of what you're showing off—all these minute details make this a very complex problem.

I forgot to talk about another important concept: two primary schools of thought around the approach to player validation. I call it the "pyramid player validation model," with top-of-pyramid and bottom-of-pyramid approaches.

The top-of-the-pyramid model is the opinion that "we are the tastemakers, we are the gods of design. We create something that we like, and because we like it, the world will like it." In this scenario, you don't need a lot of external validation. It's more of a Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, or Rick Rubin approach. Believe in yourself; you are the tastemaker. The only issue is, do you have great tastemakers on your team? A prototypical example of this approach, at least historically, is Blizzard.

Then there is the bottom-of-the-pyramid validation, which is about external validation by players. The philosophy is that you shouldn't make a game for yourself because you may not be the target audience. Instead, you should be great at getting feedback from your target players and have them help drive the design. Riot, for example, is famous for being "player-first." When you look at the success of League of Legends, it was through a lot of external player feedback that they were able to take what was a janky Warcraft 3 mod and incrementally improve it to become one of the biggest games in the world.

Which approach is right? I believe you need both, depending on the stage of the game. Start with your own design of what you think would be good, and then as you get more data and players, shift toward a more data-informed approach to iteration.

I'm out of time, so I apologize for not structuring this discussion better. There's a lot more to say, so maybe we can revisit this. But as a quick recap:

Too many execs and investors view product validation in too simple, binary a way. It's not a checklist; how you do it is material to the value you get.

There's only so much you can validate, and some things you're looking for are in that illegible margin. Be careful of what you try to force to be measured or be predictive about when it may not even be possible.

Some level of product validation is possible and valuable, but it's got to be simple. Many of the frameworks I've seen were too complex. It also depends on the stage of development, and as with so many things, the devil is in the details. Execution matters, the details matter, how you do it matters, and who does it matters. Be careful.

I'm going to cut this one short again. Thank you for tuning in. If you like this content, find it valuable, or have disagreements, please comment. Otherwise, please like, share, and subscribe. It all helps. I hope to catch you all next week. Bye.