Over the years, I’ve watched the same validation mistakes repeatedly kill games or waste millions in development costs. Different studios, different genres, different budgets—same failure patterns.

Studios conducted extensive player tests, including focus groups, surveys, and playtests with hundreds or thousands of players. The data came back positive, with high satisfaction scores, statistically significant results, and greenlights from leadership. And yet, the games launched and failed.

Meanwhile, some of the biggest hits—games that became genre-defining—barely tested at all before committing to their vision. PUBG didn’t survey players about whether battle royale would work. Brendan Greene just built it.

The studios that succeeded often understood something the failures didn’t: validation isn’t science, it’s art. They know when to trust one designer’s taste over a thousand players’ opinions—and when to do the opposite.

Here’s the framework I’ve developed for knowing when to trust your taste and when to trust your players.

Executive Summary

Validation is art, not science. You must trust tastemaker judgment for radical innovation, but use player data for proven models.

Most studios don’t fail by picking the wrong approach. They fail from “invisible” problems in their process.

These invisible failures are:

Broken Methodology: Running tests that look scientific but are flawed, yielding worthless data.

Wrong Tastemakers: Committing to a “top of the pyramid” vision when the person at the top has bad taste.

Validation Theater: Using over-intellectualized frameworks that look rigorous but give your team nothing they can actually build or execute.

The Validation Pyramid: When to Trust Taste vs. Data

I’ve spent years working with designers across game studios, trying to understand why some validation approaches work while others fail spectacularly. This framework emerged from those conversations and observed patterns. It’s not backed by comprehensive academic research—it’s a mental model, a thinking tool for navigating the art/science tension in product validation.

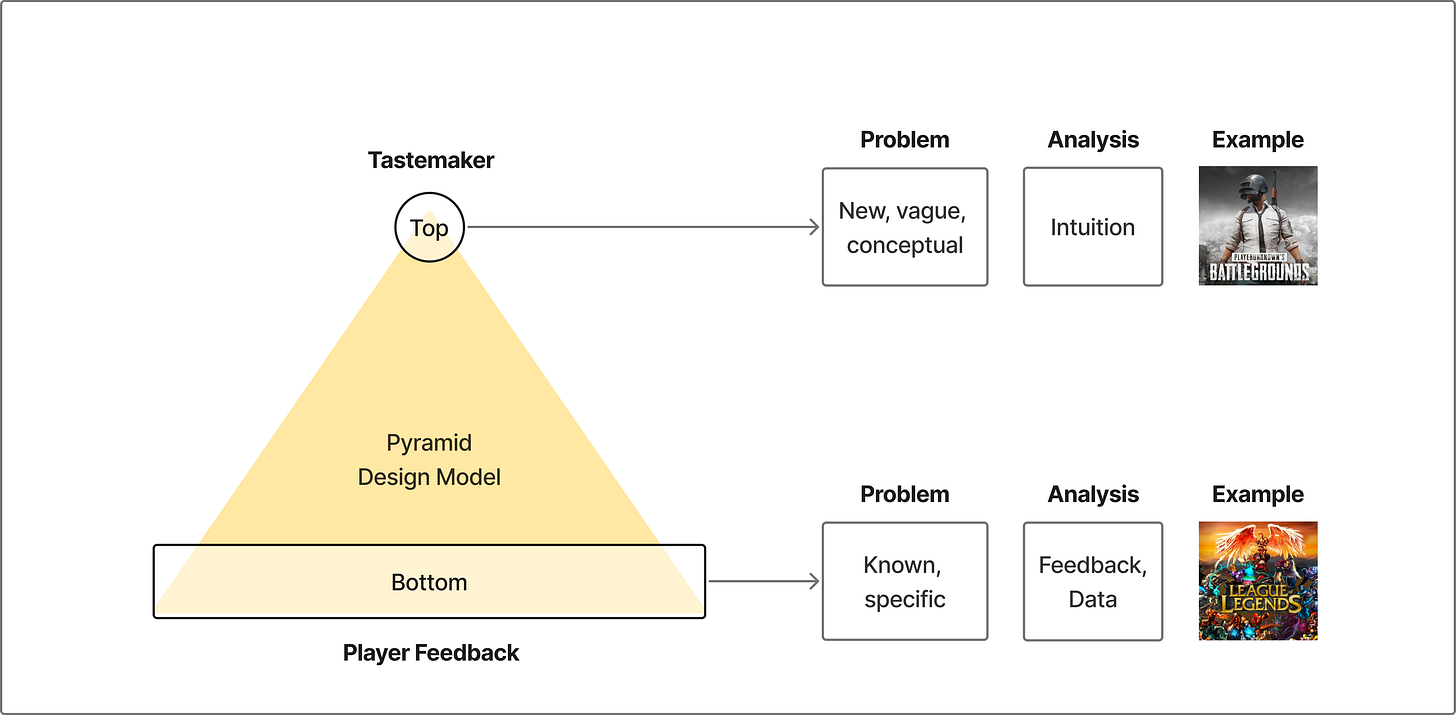

Think of validation using the “Pyramid Design Model”. At the top sits one person—a designer, creative director, tastemaker—making design decisions based on judgment. This is Steve Jobs territory: “People don’t know what they want until you show it to them”. At the bottom sit thousands of players generating data through feedback and behavior—the world of surveys, A/B tests, and statistical significance.

The critical question isn’t which approach is right. It’s which approach matches your level of innovation.

Brendan Greene created battle royale. Before his work in ARMA and H1Z1 King of the Kill, there was no “battle royale hill” to climb. Players couldn’t give feedback on whether the concept would work because the reference point didn’t exist. Brendan Greene had to trust his vision that dropping 100 players onto a shrinking island would be compelling.

Riot turned the Warcraft III DotA mod into League of Legends using extensive player feedback to refine champions, items, and meta. Players provided meaningful signals because they understood MOBAs. Marc Merrill describes their philosophy: “When we’re faced with difficult decisions, we always ask: What’s best for the player?”

The difference? Player feedback optimizes you toward the top of your current hill. Players evaluate based on what they know. Perfect for optimization. But if you’re trying to find a new peak—a new genre, an untested mechanic—asking players for direction is asking people at the bottom of one hill to tell you if a different hill they can’t see is taller.

I’ve seen this pattern destroy studios: they use optimization techniques (player feedback, A/B testing, incremental iteration) when they need discovery (vision, taste, willingness to jump hills). They optimize their way to the top of the wrong hill.

When Your Tastemaker Is Wrong

Here’s the uncomfortable reality that makes validation even harder: operating at the top of the pyramid only works if the tastemaker has good taste. What if your creative director is wrong?

I’ve seen projects start with a tastemaker who seemed right—strong portfolio, confident vision, team buy-in—only to discover months or years later that their taste didn’t match what would actually work. The team committed to the top-of-the-pyramid approach, trusted the vision, and climbed the wrong hill for months or years.

This is one of the most challenging problems in validation because it is difficult to test taste in advance. But there are warning signs:

Fall back on first principles. Why should this concept work? What player needs does it address? If the tastemaker can’t articulate the logic beyond “trust me,” that’s a red flag. Vision needs rationale, not just confidence.

Seek external tastemakers with relevant expertise. Show the concept to 3-5 people whose taste you respect in the relevant domain. Do they see the vision? Do they get excited? If they’re lukewarm or confused, that’s a signal. You’re not looking for approval—you’re stress-testing whether the vision makes sense to other people with good taste. Note, however, that the biggest opportunities will be the most controversial: a “secret.”

Validate the validator. Past success in a different domain doesn’t guarantee taste in your current one. A designer who shipped a successful match-3 game might not have the right instincts for a hardcore strategy game. Domain expertise matters.

Watch for vision drift. If the creative vision keeps changing fundamentally every few weeks, that’s not iteration—that’s a tastemaker who doesn’t actually know what they want. Vision should evolve and sharpen, not pivot constantly.

The hardest decision: if your tastemaker is wrong and you’re committed to the top of the pyramid, you might need to change who’s at the top. Better to face this early—painful as it is—than waste months or longer climbing the wrong hill. I’ve seen studios delay this decision because it feels brutal, but keeping the wrong tastemaker is more brutal. It kills the project.

The 50-50 Gender Split That Revealed Worthless Data

Here’s why broken validation is more dangerous than no validation.

A mobile studio I know ran a CSAT survey to validate a new feature before greenlighting production. They distributed it through an offerwall—players took the survey in exchange for hard currency in another game. Thousands of responses. Statistical significance achieved. High satisfaction scores. Green light given.

One problem: the players didn’t read the questions. They tapped randomly to get their currency reward. The entire dataset was garbage.

The team caught it because someone noticed the male-to-female ratio was 50-50. For that game, it should have been 80-90% male. That anomaly triggered an investigation. They discovered players were gaming the survey.

Here’s what makes broken tests so dangerous: they’re invisible. They look identical to good tests in your spreadsheet. Both give you numbers. Both achieve significance. Both generate the confidence that executives desperately want. The only difference is methodology—and most people never audit that.

I’ve seen this pattern repeat in different forms: Wrong incentives where players game surveys. Wrong context where low-fidelity prototypes can’t be meaningfully evaluated. Wrong wording that biases specific responses. Wrong sample where the wrong personas judge your game. Wrong interpretation where correlation becomes causation.

Any of these invisibly contaminates your data. In science, peer review catches flawed methodology. In game development, launch day is your peer review. By then, you’ve already bet on flawed data.

The Danger of Over-Intellectualization

There’s another way validation fails that’s particularly insidious: it looks sophisticated, scientifically rigorous, and impressively complex—but yields absolutely nothing operational or gives a wrong result.

The Head of R&D for a major game studio recently told me, “The vast majority of these studies are useless. These complicated motivational frameworks are generally not useful. You can do a lot of surveys, but they tend to be fluffy and lead to things your team will never understand how to execute.”

I’ve seen this pattern repeatedly. A studio hires a research firm or builds an internal research team. They develop elaborate player personas based on psychographic segmentation. They create motivational frameworks with names like “The Achievement-Oriented Competitive Socializer” and “The Mastery-Driven Aesthetic Explorer.” They conduct studies that produce detailed reports with charts, statistical analyses, and sophisticated academic methodologies.

Then they try to use it. And nothing happens.

The design team examines the personas and asks, “Okay, so what do we build for the Achievement-Oriented Competitive Socializer?” The answer is unclear. The framework is too abstract. The motivations are too general. The insights don’t translate into concrete design decisions.

The problem isn’t that the research is wrong—it’s that it’s not useful. You can have perfectly valid psychological frameworks that tell you nothing about whether your game loop is fun, whether your monetization will work, or whether players will understand your core mechanic.

This type of validation failure is particularly dangerous because it creates the illusion of rigor. Leadership sees impressive decks. Money gets spent. Time passes. Teams feel validated in their approach because they have “data-driven insights.” But when you ask what actually changed in the game because of the research, the answer is often nothing—or worse, the wrong result based on academic fluff.

The solution isn’t to avoid research—it’s to demand operational clarity. Before you invest in any validation methodology, ask: “What decision will this help us make? How will the answer change what we build? Do we actually understand and believe these fancy academic frameworks?” If you can’t answer clearly, the validation is probably intellectual theater rather than practical and correct insight.

Simple, concrete validation—“Players churned at this step in the tutorial. Let’s test three different approaches and measure funnel drop-off”—almost always beats elaborate theoretical frameworks. Focus on answering specific questions that directly change what you build.

When Asking Players About Innovation Kills It

I’ve seen two different studios make the same validation mistake. Both were designing new games and wanted to validate concepts with players.

They surveyed hundreds: “Which genres do you enjoy? MOBA? City-building? RPG?” Players selected multiple options. The data came back clear—players loved all three genres. They even believed that all three could be achieved in a single game.

Both studios created games combining three genres. After all, the data showed players wanted this. Both games launched. Both failed.

The problem wasn’t the data—it was interpretation. Players who like three different genres don’t necessarily want those genres mashed together. And it’s difficult for players to grasp what that hybrid would actually mean. Players want great MOBAs. Great city-builders. Great RPGs. Not a confusing hybrid that tries to be everything and becomes nothing.

Players will tell you what they like. But “what do you like?” isn’t the same as “what should we build?” The first question measures taste. The second requires vision. You can’t crowdsource vision from survey data.

Three Ways Player Feedback Generates Noise

Even when your methodology is sound, you face signal vs. noise problems. Through working with studios on validation, I’ve identified three ways player feedback generates noise instead of signal:

The conceptual gap. Players can’t evaluate what doesn’t exist yet. You’re not testing your game—you’re testing their ability to imagine what your game could be. Novel concepts need top-of-pyramid validation with small groups who can envision what doesn’t exist.

The persona mismatch. Asking the wrong players about your game is like asking vegans which hamburger they prefer. Test a hardcore strategy game with casual match-3 players and you’ll get clear, statistically significant, ultimately useless feedback. The data is accurate. The sample is wrong.

The articulation gap. Even expert players may struggle to explain what’s wrong. They feel something is off. They can tell you they’re not having fun. But they can’t necessarily articulate why or what would fix it. Their feedback is real—their diagnosis might be completely wrong. This is why behavioral data matters more than stated preferences.

Quality beats quantity in early validation. Five players who match your target persona and can envision what doesn’t exist generate more signal than a thousand random players. As your concept becomes more concrete, these noise problems decrease and large-scale player feedback becomes more valuable.

Why Perfect Validation Can’t Predict Execution

Here’s what no validation methodology will tell you: whether you’ll execute well enough for any of it to matter.

BioWare’s Anthem playtested well. EA CEO Andrew Wilson reported players were satisfied through 30 hours of content. The validation wasn’t fundamentally broken—players did enjoy what they played. The problem was execution.

The game spent seven years in development but didn’t truly enter production until the final 18 months. Leadership couldn’t provide consistent direction. The Frostbite engine created technical challenges. Content systems weren’t ready. The live service loop felt like a grind.

Validation couldn’t predict any of this. It couldn’t tell you whether the endgame would have enough content, that technical issues would plague launch, or that thousands of small decisions in UI, progression, and social features would fail to come together.

Even perfect validation doesn’t guarantee success. Between concept and launch sit thousands of execution decisions that validation can’t predict. This is why treating validation as pure science is dangerous. It creates false certainty. You gather data, reach significance, and believe you’ve eliminated risk. But you’ve only validated part of the equation.

The best studios I’ve worked with combine smart validation with a ruthless focus on execution. They never confuse validation with execution. Validation tells you what to build. Execution determines whether you build it well.

Matching Validation to Development Stage

Here’s what I’ve learned about validation across development stages:

Pre-Production: Trust Tastemaker Vision (But Validate the Tastemaker)

You’re validating whether the core idea resonates. Operate at the top of the pyramid. A lead designer or small team decides the vision based on taste and judgment. But make sure your tastemaker has good taste—test with 3-5 external tastemakers whose judgment you respect. Use fake ad CTR tests to signal interest, but the tastemaker still decides what to build.

The signal you’re looking for: Does this feel genuinely new and compelling? Does the logic for why it should work hold up under scrutiny?

Production: Mix Designer Judgment with Curated Feedback

You’re validating whether mechanics are fun and the game is learnable. Internal playtesting with target-persona staff (watch behavior, not words). Small-group playtests with 20+ players—qualitative feedback and surveys for directional feedback.

Avoid over-intellectualized frameworks. Focus on concrete, operational questions: “Do players understand this mechanic? Where do they churn? What changes retention?”

Soft Launch: Let Data Drive Economics

You’re validating whether players will engage and if unit economics work. Test with real money in limited markets. Hundreds to thousands of players generating behavioral signals. Early retention via funnel analysis, A/B test features, pricing, and monetization. Analyze LTV, ARPU, retention cohorts, and spender behavior.

Signal to trust: Actual spending behavior, not stated willingness to pay.

Hard Launch: Pure Market Validation

You’re validating what creative drives cost-effective installs, ROAS, and the ability to drive full project economics. Test marketing across channels to identify where your audience resides and how far you can scale before encountering diminishing returns.

Who decides: Market response determines what works.

The progression: You start at the top of the pyramid (tastemaker vision) in pre-production, then gradually move down through production and soft launch, reaching the bottom (pure data) by the time of the hard launch. Match your methodology to your stage, validate your tastemaker early, and avoid intellectual theater that yields no operational results.

Takeaways

Validation is art, not science—and it requires the right artist. Novel concepts require tastemaker judgment (PUBG), but only if your tastemaker has good taste. Proven models require player data (League). Match your approach to your innovation level, then validate that your validators are actually good at validation.

Broken validation tests are invisible. Statistical significance doesn’t mean your methodology was sound. Question your incentives, sample, context, and interpretation. The most dangerous validation isn’t no validation—it’s broken validation that looks rigorous.

Avoid validation theater. Over-intellectualized frameworks and complicated personas often yield little in terms of operational value. Before investing in any validation methodology, ask: “What decision will this help us make? How will the answer change what we build?” Simple, concrete validation beats elaborate theoretical frameworks.

Quality beats quantity in early validation. Player feedback generates noise through conceptual gaps, persona mismatches, and articulation gaps. Five right players generate more signal than a thousand random ones.

Validation predicts interest, not execution. Even perfect validation can’t tell you if you’ll execute well. The gap between validated concept and delivered product determines outcomes. Combine smart validation with ruthless execution focus.